2020-03-28 • Halifax • Review by Allis Kolynchuk

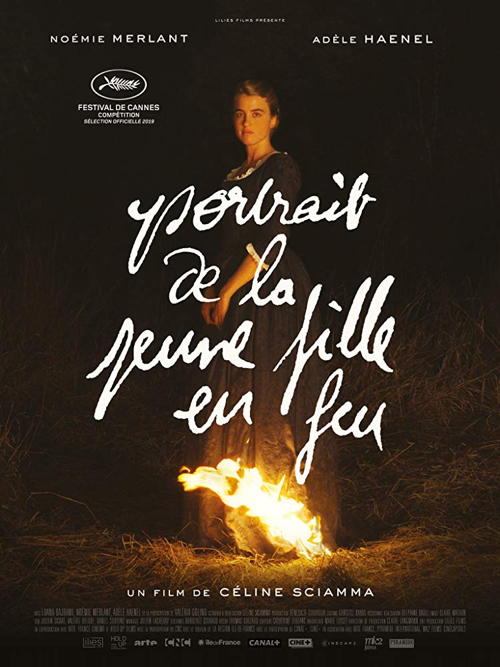

Set near the end of the eighteenth century on an isolated island in eastern France, Portrait of a Lady on Fire (Portrait de la Jeune Fille en Feu) is a historical romance that does well to portray the feeling of love. I don’t just mean the usual trope of fleeting ecstasy that comes from meeting another. This film unapologetically portrays the entire, full depth of a love story between two young women. Portrait of a Lady on Fire is a Victorian-era account of love that relates in a timeless way to modern queer culture. Marianne (Noémie Merlant) is an independent travelling painter who arrives at an oceanside estate on commission to complete the wedding portrait of Héloïse (Adèle Haenel). Héloïse is a free-thinker who recently returned home upon her mother’s request to be arranged into marriage. In an act of rebellion, Héloïse refuses to pose for the wedding portrait, so Marianne is obligated to paint her in secret. Intimacy, attraction and intense romance develops between the two as Marianne studies the mannerisms of Héloïse closely by day in order to complete her portrait at night.

Portrait of a Lady on Fire is a slow-burning and emotional film. As viewers, we feel the cringe at moments of mounting tension. The hints of heightened curiosity and amorous glazes between Marianne and Héloïse could be just as well directed at us. The slow progression leading to the physical intimacy between the two women and the vulnerability that follows is relatable in a very human way. Such as in life, we are not given what we expect right away and sometimes we are not given it at all. The film does well to leave us with the visceral feeling of what it is actually like to fall into and be caught in the midst of a queer romance.

Filming takes place on a weathered peninsula in the Brittany region of northwestern France. Rocky cliffs and moody ocean swells amplify our empathy as Marianne and Héloïse experience the scope of their love story. The rhythm is uplifted by a soundtrack inspired by Vivaldi’s classic Four Seasons. The atmosphere of the film remains foreboding and tragedy looms, as the reality of Héloïse’s impending arranged marriage remains ever-present. At the end of the film we are left with the torn sense of longing that comes from parting. We become aware that although circumstances may not allow for all romances of the flesh to last, time and memory allow for a continuation of meaning. At one point in the film, Marianne explains to Héloïse that in a painting, as well as in life, “Your presence is made up of fleeting moments that may lack truth”. Héloïse replies “Not everything is fleeting. Some feelings are deep”.

Filming takes place on a weathered peninsula in the Brittany region of northwestern France. Rocky cliffs and moody ocean swells amplify our empathy as Marianne and Héloïse experience the scope of their love story. The rhythm is uplifted by a soundtrack inspired by Vivaldi’s classic Four Seasons. The atmosphere of the film remains foreboding and tragedy looms, as the reality of Héloïse’s impending arranged marriage remains ever-present. At the end of the film we are left with the torn sense of longing that comes from parting. We become aware that although circumstances may not allow for all romances of the flesh to last, time and memory allow for a continuation of meaning. At one point in the film, Marianne explains to Héloïse that in a painting, as well as in life, “Your presence is made up of fleeting moments that may lack truth”. Héloïse replies “Not everything is fleeting. Some feelings are deep”.

Under the guidance of writer/director Céline Sciamma, Portrait of a Lady on Fire was created with a decidedly female gaze. Character development is intricate and allows for the female characters to be viewed as subjects rather than as objects. Such a female gaze is rare in a film industry that is, to be blunt, dominated by white and cis-gender males. Sciamma is an activist and a prominent member of the feminist community in France. She has a filmography of independent queer films that includes Water Lillies (2007), Tomboy (2011) and Girlhood (2014). Equality, inclusion and gender parity in the film industry is a genuine cause of Sciamma’s. This is apparent as Portrait of a Lady on Fire was created by a mostly female team. There are only a handful (less than five) short dialogue lines spoken by men and a complete lack of recurring male characters. A decidedly female gaze allowed Adèle Haenel and Noémie Merlant the liberty to fully explore the relationship between their characters. They were able to depict love between women from a woman’s point of view, and the result is timeless.

While viewing Portrait of a Lady on Fire, I was stuck by the contrast between the film’s relevance to modern queer culture despite the time period during in which it is set. The late Victorian era was a time of generalized inequality. We are reminded at many points in the film that women during that era were disadvantaged economically and socially. One scene that struck me was set at an art show that Marianne was attending. She had decided to submit her paintings under her father’s name because doing so allowed her paintings to be valued at a much higher level than if she had submitted then in her own, female name. Wardrobe design is reflective of the limited utility of female outfits during the Victorian era; tight corsets and heavy, draped dresses prevail. However, Sciamma’s female gaze ensures that the film continues to be a statement against conventions. We see hints of the female liberation that was stirring near the end of the eighteenth century; independence is a strong trait in all characters. Ideas of classism are also challenged as the relationships between characters of different social standings are seen with intentions friendship and solidarity.

Equality is a common stance of queer culture, no matter what generation or era. I believe that the pursuit of equality and how it is depicted in Portrait of a Lady on Fire is what allows the film to connect in a heartfelt way to our modern community. Love itself is also, of course, timeless and the very enthralling depiction of it in this film will stay with you for days.

Since its European release in September 2019, Portrait of a Lady on Fire was the first film directed by a woman to win the Queer Palme at last year’s Cannes Film Festival in France. It was also chosen by the National Board of Review as one of the Top Five Foreign Language Films of 2019. Other awards include the LGBTQ Film of the Year at the Dorian Awards and Best Cinematography at the César Awards. It was widely released in February 2020 and enjoyed a theatrical run locally at Cineplex Park Lane.

Since its European release in September 2019, Portrait of a Lady on Fire was the first film directed by a woman to win the Queer Palme at last year’s Cannes Film Festival in France. It was also chosen by the National Board of Review as one of the Top Five Foreign Language Films of 2019. Other awards include the LGBTQ Film of the Year at the Dorian Awards and Best Cinematography at the César Awards. It was widely released in February 2020 and enjoyed a theatrical run locally at Cineplex Park Lane.

Watch for it as a special Criterion collection edition in June 2020.