This is not an attack or a call to shut down a queer bar. It is a look at what happens when a venue markets itself as a “safe space” and is then asked what that means.

Everything in this piece comes from public documents, earlier reporting and interviews with community members, event organisers and former staff. Where possible, information has been corroborated by more than one source. When a business presents itself as a safe space for 2SLGBTQIA+ people, that claim becomes a matter of public interest.

Be You Bar in Charlottetown, which public records in the PEI Business / Corporate Registry list as being owned by Johnny Barlow, opened this year to real excitement. A July feature in Wayves introduced it as “a safe, inclusive and long-awaited 2SLGBTQIA+ addition” to the bar scene and quoted management promising metal detectors, a do‑not‑admit list, staff bystander‑intervention and first‑aid training, security cameras and “customer code of conduct” cards for patrons reported for hate or violence. Tourism and business listings now describe Be You as the Island’s first 2SLGBTQIA+ nightclub and “safe space” for the community, friends and allies.

A SaltWire article titled “Queer nightclub in Charlottetown aims to offer a safe space” described Be You as more than a nightclub, saying it aimed to “create a safe home for LGBTQIA2S+ Islanders and their allies,” and quoted business manager Serge Savoie: “It was created to save lives…” That language positions Be You as a kind of community service or centre, yet according to the PEI business and corporate registry it is a privately owned, for-profit bar with a single proprietor rather than a non-profit run by a volunteer board. When a for-profit bar presents itself as a community “safe space” or “home,” that gap between branding and structure is worth noting.

A former employee told Wayves that as of early November they were not aware of any formal safer‑space or bystander‑intervention training being delivered to staff

In early November Wayves began hearing from people who were worried about how those safe space promises were playing out. A former employee, who asked to remain anonymous, told Wayves that as of early November they were not aware of any formal safer‑space or bystander‑intervention training being delivered to staff, in contrast to public commitments. Two other former staff and a volunteer described similar experiences and said they mostly learned to cope with busy nights and security situations on the fly. These are their recollections, not legal findings, but the pattern is consistent.

That former employee also raised concerns about how risk inside the building was handled. They said that when they suggested routine washroom checks, based on what they had been taught in a college program, they were told bathrooms were private and should not be monitored. They recalled discussion of a do-not-admit list, but did not see a consistent, documented process for implementing it at the door.

A second anonymous source, who first volunteered as a painter and then worked behind the bar, described a rushed opening with little structured training. They said they felt under pressure to keep serving guests they believed appeared intoxicated. They reported witnessing conduct they believed created safety risks, describing sexual activity and suspected drug use. They told Wayves they were not aware of a clear incident‑reporting process or HR route to raise safety concerns. Again, these are allegations about their time there, not court‑tested facts, but they give a picture of how safety looked from behind the bar from the perspective of a former volunteer.

That kind of concrete, written expectation is close to what safer‑nightlife toolkits for queer venues recommend: clear standards, visible consequences and a plan for responding when harm occurs.

Event organisers and patrons painted a mixed picture. One organiser said they did not see a clearly advertised safer-space policy or code of conduct, did not receive written guidance in advance, and saw heavily intoxicated guests leave without clear checks on how they were getting home, while a patron at a Halloween drag show described the space as friendly but chaotic, with long waits at the bar and chairs disappearing and reappearing as the room filled. By contrast, Be You Bar’s business manager (who promotes events under the IntenseFire Productions brand), set out a detailed consent-centred policy on an Eventbrite listing for an event at Be You Bar, promising that organisers would monitor behaviour and substance use and warning that anyone violating those guidelines would be asked to leave after a single incident. That kind of concrete, written expectation is close to what safer‑nightlife toolkits for queer venues recommend: clear standards, visible consequences and a plan for responding when harm occurs.

Wayves asked Be You these questions directly to in early November, asking about safer‑space policies, staff training and reporting mechanisms. Be You did not provide answers to the specific questions by publication time. Instead of a response, on November 9th, cease‑and‑desist letters on Be You letterhead were sent to this writer, the publisher of Wayves Magazine, and to a third‑party employer that has nothing to do with this story. Wayves has reviewed documentation relating to the cease-and-desist letters and relevant public listings.The letters accused Wayves writers of spreading false and defamatory information, demanded that anything critical be retracted, that a public apology be issued, that the journalist be terminated from any and all employment, and warned that Be You will pursue legal action if all three entities do not comply. All three letters emphasise that the bar exists to provide a “safe place” for the queer community.

There's substantial irony in Be You declaring they're centering on safety, and then bullying a journalist instead of responding to questions.

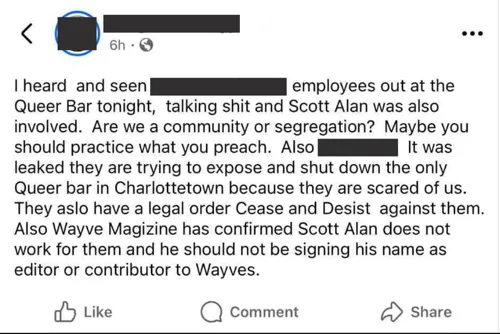

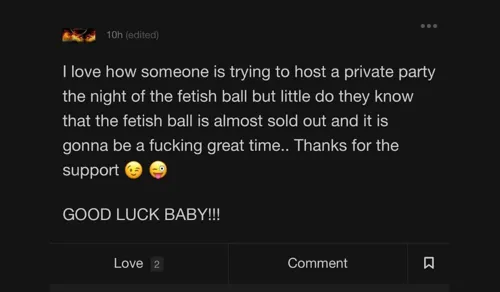

A week later, a manager from Be You Bar posted on Facebook that employees of the above mentioned third-party employer and I (Scott Alan) had been “talking shit” at a Be You Bar event and accused a separate local non-profit of trying to shut down the “only queer bar in Charlottetown,” asking “are we a community or segregation?” and saying there was a legal cease-and-desist order against all of us; at the time of the night they described, this writer was in Toronto and not on the Island at all. Around the same period, the same manager, who was promoting under their IntenseFire Productions brand, posted about a private party happening the same night as one of their events and, in a mocking tone, wrote “GOOD LUCK BABY!!!” while boasting that their own show was almost sold out.

The above is included not because social-media arguments are the centre of the story, but because it shows how quickly safety questions can be reframed as personal attacks. It is a striking look for a venue that centres its public image on care and safety to respond to quiet questions with formal demands in the form of cease‑and‑desist letters to a small queer magazine and an unrelated employer, while their manager plays out disputes through taunting public posts.

Across queer and social‑justice spaces, people are rethinking the phrase “safe space.” In the widely shared poem An Invitation to Brave Space, Micky ScottBey Jones writes that there is “no such thing as a safe space,” only spaces where people work together, imperfectly, to reduce harm and keep listening. Safer‑space guidelines for nightlife echo that view. They stress that bars cannot guarantee safety, only reduce risk through visible policies, staff training, bathroom and floor monitoring, easy reporting options and meaningful follow‑up when something goes wrong.

Safe spaces, in the absolute sense, do not exist, especially in rooms where alcohol is served and strangers come together.

That is where Be You’s public promises and the experiences described by workers, organisers and patrons seem to diverge. This article does not say that Be You is uniquely dangerous, or that harm never occurs in other queer venues. It does not argue that the bar cannot change. It does argue that calling any bar a “safe space” is risky, and that when governments, tourism agencies and community media repeat that claim, they help set an expectation that no nightlife space can honestly meet.

Safe spaces, in the absolute sense, do not exist, especially in rooms where alcohol is served and strangers come together. Safer spaces can exist, but only when safety is treated as daily practice rather than branding. For a bar that carries so much hope for queer people on Prince Edward Island, the most important promise is not that nothing can go wrong. It is that when something does, the people in charge will welcome hard questions, listen to the answers and be transparent about what they will do next.