We Were Here is an ongoing project of writer Mary Fairhurst Breen.

Phase one was the collection of stories about young people who have died of opioids in recent years. One of them was her own daughter, Sophie Breen. Ten of the stories from Ontario have turned into animated short films and are receiving recognition at film festivals in Canada and internationally.

Phase two is the collection of stories from across Canada about people who died in the early years of the AIDS crisis. The response to both health crises bear striking similarities, and those lost deserve to be remembered. The project is both a memorial and a call to action.

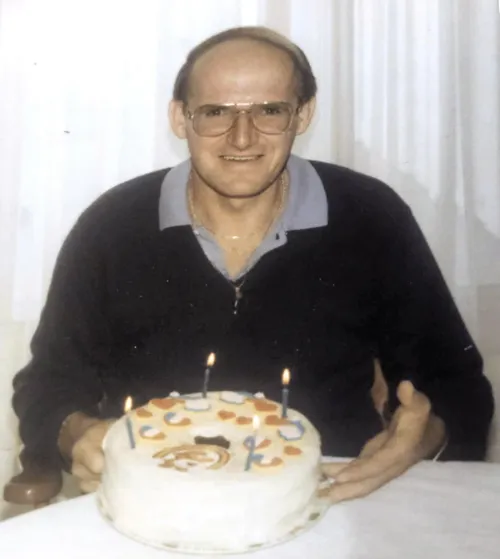

Allan Hickox and Stuart Hickox

Imagine your lifelong friends - members of your close knit faith community - refusing to touch your ambrosia salad at the church potluck. Imagine being hounded by reporters outside your front door and jeered at by neighbours at the grocery store. That’s how it was for Jean Hickox, before and for some time after the death of her son Allan in 1987, the first confirmed AIDS fatality on Prince Edward Island.

Now imagine you are a teenage boy watching this unfold within your own family. That’s how it was for Stuart Hickox, whose father was Allan’s cousin. He decided to get as far away as possible from the judgement and scorn, and to deadbolt his own closet door. Stuart didn’t come out until he was fifty years old. When he was finally ready, he did it on World AIDS Day 2017. The reveal was in front of a room full of dignitaries, as part of a speech he was giving in his role as Canadian director for the ONE campaign, an international not-for-profit started by Bono.

He said, “I remember as a teen that the thing I heard most often was that if Allan really was gay and had AIDS, he was getting what he deserved. Even my dad called him the Family Shame. And then in 1987, Allan died. A lot of the family avoided the funeral. His mother, Great-aunt Jean, wasn’t allowed to see the body. For me, as an adolescent from a religious family in a small community, it was so traumatic that it took me another three decades to admit (even to myself) that I too am gay.”

Although Stuart was understandably shaken by this experience, he never forgot Jean’s courageous response to the cruelty of her community. She went on CBC radio to say her son was gay, he died of AIDS and she loved and was proud of him.

In 2022, Stuart took part in Dave Stewart’s excellent “talkumentary,” Positive: When HIV/AIDS hit PEI. This led to my interview with Stuart and Dave for this project, We Were Here, which honours just a few of the lives that were cut short by AIDS thirty-odd years ago, and those lost to the current opioid crisis. My daughter Sophie Breen was one of them. To me, the two health crises bear harsh similarities.

Dave Stewart describes himself as “an accidental queer archivist” with a passion for LGBT+ social history. He first embarked on a 6-part video series called Before Grindr, which made him realize how little had been documented about the impact of HIV/AIDS on the island. In addition to finding Stuart and hearing Allan’s story, Dave’s next project, Positive, took him back to his own experience watching news of a deadly disease coming out of New York when he was in his early twenties. As a sexually active closeted gay man, he was terrified that he would die a horrendous and lonely death as a pariah. Dave’s doctor was the first person he came out to, when he made an appointment to ask for an HIV test. The doctor made the process sound as threatening as possible, telling Dave he’d go on a government registry and have to contact every man he’d had sex with if his test came back positive.

Dave went ahead despite his doctor’s dire warnings and continued to get tested every three months. He wanted to avoid spreading the virus without abandoning the joy of sex. The concept of harm reduction, through safer sex and programs like needle exchanges, really took hold in the early days of the AIDS crisis and continues to inform the response to the opioid crisis. It’s a simple premise: if people are going to engage in certain behaviours - whether others approve or not - then we need to mitigate the risks involved, because everyone deserves to live. Straight people with multiple sexual partners started getting tested in the 80s and 90s as well, and condom use became the norm for everyone, with incalculable and lasting health benefits.

Growing up, Stuart was aware that Allan was “not like the others.”

Dave has been volunteering for many years, in programs promoting men’s sexual health and youth mentorship through PEERS Alliance. It is one of many organizations across Canada whose mandate has expanded since its initial urgent AIDS response to include a more comprehensive approach to health. It works “to educate, engage, and support Island residents to build healthier, inclusive communities and to end stigma surrounding sexual health and drug use using a trauma-informed approach.”

Stuart Hickox spoke to me from the lovely rural retreat in PEI that he shares with his adult sons - the family he never would have had, had he not been scared into a traditional marriage with a woman. He says plainly, “My children exist because Allan died of AIDS. I saw what happens when you’re openly gay, and I couldn’t do it.” On the day of our interview, he had received a birthday gift from his ex-wife, who remains a dear friend.

Growing up, Stuart was aware that Allan was “not like the others.” He was creative, artistic and often described as flamboyant. He was fun, in a family of stiff and reserved aunts and uncles. Stuart isn’t entirely sure how it came out that Allan was sick with AIDS, but the hysteria that ensued was borne of the particular kind of fear that can propagate on a small homogeneous island. Stuart notes that even during Covid, when PEI had extremely tight restrictions, people were very wary of their neighbours, going so far as to put warning signs on the lawns of those who were sick. “Go back forty years and make it about gay men, and you can just imagine what it was like,” notes Stuart.

When Allan died, Stuart’s father refused to go to the funeral, where he claimed he could get AIDS by shaking hands with his “faggot friends.”

When Allan died, Stuart’s father refused to go to the funeral, where he claimed he could get AIDS by shaking hands with his “faggot friends.” Stuart knew his attitude was wrong and mean-spirited but did not have the capacity to defend Allen. Nor did he have the wherewithal to escape the box he was in, for reasons that have become clearer as he’s explored his family history. When Stuart did a university term in France, his grandfather, a conservative minister, wrote him a letter admonishing him to avoid the pleasures of the flesh. He was warning him, in no uncertain terms but without saying the words, that he could not be gay. Stuart got the message. On his wedding day, he knew he was making a conscious choice to deny who he was.

It turns out his grandfather had experienced parental rejection due to a terrible family tragedy. He filled the void with religious zeal. He moved his family from Wales to Alberta to PEI, ultimately wielding a great deal of influence from the pulpit but remaining sad and lonely his entire life, and passing on his trauma in complex ways. Into this unresolved situation landed Allan, and then Stuart.

While determinedly straight in his personal life - to the point of not knowing who RuPaul was - Stuart broke the mold in his professional life, becoming involved in the fight against HIV/AIDS in Africa… Which brings us back to that posh event in Ottawa on World AIDS Day 2017. Stuart remembers the silence that immediately followed his very public coming out. But his story about Great-aunt Jean’s response to injustice and stigma perfectly reflected the theme of the evening.

He told the crowd, “Keep in mind, this was a woman born before electricity in rural PEI in a fundamentalist religious society that didn’t value women and where women were expected to stay in their place and be seen, not heard. Doesn’t that sound familiar? As I considered this story for tonight, it occurred to me that these are the same circumstances we find women dealing with in communities we are struggling to help today. So while Great-aunt Jean’s courage was remarkable in itself, it’s only very recently that the full meaning of her actions has dawned on me, and why her story is relevant.”

He told the crowd, “Keep in mind, this was a woman born before electricity in rural PEI in a fundamentalist religious society that didn’t value women and where women were expected to stay in their place and be seen, not heard. Doesn’t that sound familiar? As I considered this story for tonight, it occurred to me that these are the same circumstances we find women dealing with in communities we are struggling to help today. So while Great-aunt Jean’s courage was remarkable in itself, it’s only very recently that the full meaning of her actions has dawned on me, and why her story is relevant.”

A few years later, Stuart found himself in a pitched battle with the Canadian government over international aid for HIV/AIDS. Much public intervention and a threat to embarrass the PM at the Montreal Pride parade helped ensure that the money was released. Later that month, Stuart visited Allan’s grave on PEI and realized that the funding decision came on the anniversary of his death.

By Mary Fairhurst Breen • Toronto • 2025-09-05

By Mary Fairhurst Breen • Toronto • 2025-09-05